During my time as an undergraduate teaching assistant for an algorithms course at the university, I’ve noticed that dynamic programming (DP) is a topic that frustrates many learners when they first encounter it. If this was not evident by the feedback I gave on homework, it was certainly evident from the students who voiced their frustration during my office hours. I will try my best to explain it as simply as I can, but one must practice to truly become familiar with this technique. For those that are familiar with dynamic programming but struggle to solve problems in it, the sections on solving 1-dimensional and multi-dimensional problems may be more useful and worth skipping ahead to.

Table of Contents

- Definitions

- Top-Down Approach

- Bottom-Up Approach

- Solving 1-Dimensional Problems

- Solving Multi-Dimensional Problems

- Conclusion

Definitions

Depending on who you talk to, DP is a bit different. Shayan Oveis Gharan, my professor for algorithms, said during my lecture that DP is simply induction. A common way (perhaps the most common way) to write a proof of correctness for a DP algorithm is to use induction. Robbie Weber, the professor I taught for, said that induction is unnecessary for understanding DP, and that you should simply write a recurrence and the algorithm flows from that. I tend to think Robbie’s thoughts on teaching DP to be more practical.

So dynamic programming is an algorithmic technique to optimally solve problems that have both an optimal substructure and overlapping subproblems attribute. These 2 attributes to a problem can be found in the problem of calculating the \(n^{th}\) number in the Fibonacci sequence.

\[f(n)=\begin{cases}0 & \text{if } n = 0\\ 1 & \text{if } n = 1\\ f(n-1) + f(n-2) & \text{otherwise}\\ \end{cases}\]The above recurrence solves the problem of getting the \(n^{th}\) number in the Fibonacci sequence. Notice how it is recursive in nature. Having an optimal substructure means that the optimal solution of \(n\) will likely involve finding the optimal solution for its subproblems, like \(f(n - 1), f(n - 2), f(n - 3)\), and so on. The second property to notice is that if we were to run a naive algorithm (the one that is a direct programmatic translation of the above recurrence without anything fancy), then we will be recomputing subproblems. This is where overlapping subproblems comes into play.

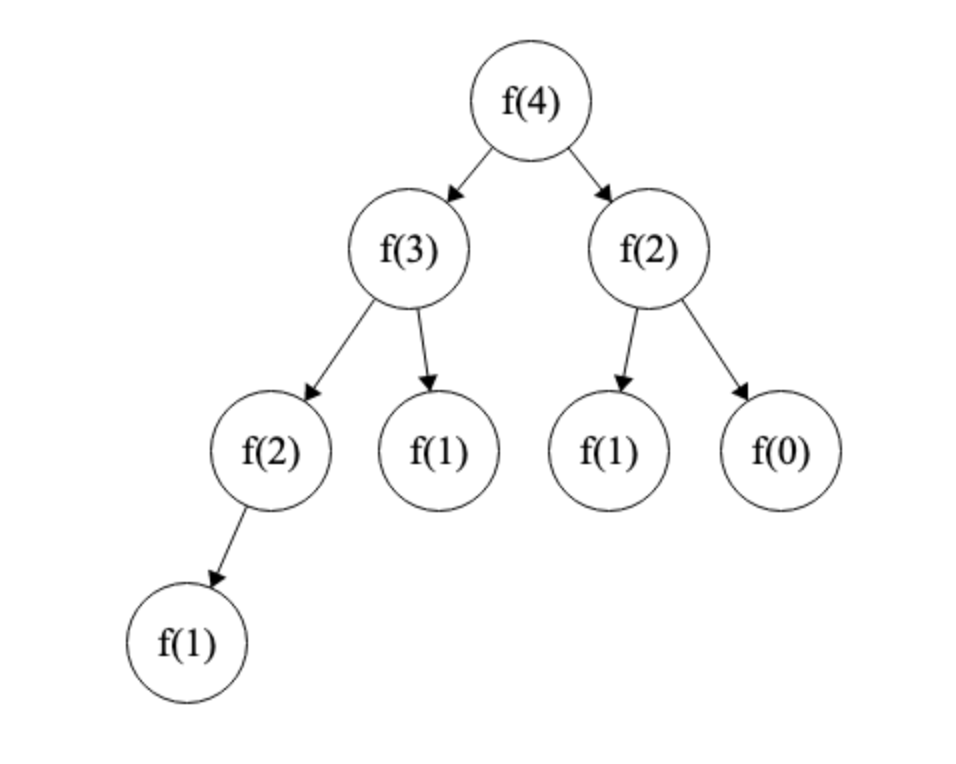

The tree of calls on \(f(4)\) would create the following tree above. Notice how we are recomputing certain inputs of \(f\) more than once. We don’t need to compute \(f(n - 2)\) more than once, but in a naive approach of just brute forcing, we would be computing it twice. We can imagine for large inputs of \(n\), we will get a very poor time complexity due to the recomputation of entire branches. Dynamic programming will optimize our algorithm such that we will only compute each subproblem exactly once, which will avoid recomputing the solutions to these expensive subproblems.

To achieve this, we will cache the results of our function calls when they finish. In the instance that we are about to compute \(f\) on a particular input that has already been seen and computed, we will check our data structure to return the cached value instead of recomputing. This technique is called memoization. We can achieve this with an \(n + 1\) element array \(A\). When we finish computing \(f(x)\), we will store the result in \(A[x]\). Then when we come across the situation where we may have to recompute \(f(x)\), we will first check to see if there is a result computed in \(A[x]\) before considering to recurse on \(f(x)\). Once we see that the value is present, we don’t recurse and instead we use the cached value.

The other approach is a method of tabulation. We start by computing \(f(0)\) and \(f(1)\), before computing \(f(2)\) and other larger subproblems. This approach is typically done iteratively rather than recursively.

The two approaches here will be covered in some more detail in the next 2 sections on top-down and bottom-up dynamic programming. Memoization is often associated with the top-down approach, and tabulation with the bottom-up approach. To note, these 2 approaches, memoization and tabulation, are not mutually exclusive. And recursion and iterative solutions can be translated to one another, though not intuitive. So the distinctions are blurry. So in my personal opinion, it is better to think of a recursive and iterative solution, and throw memoization at the problem when needed (which is often the case).

Top-Down Approach

The following algorithm written in python is the naive recursive solution to finding the \(n^{th}\) Fibonacci number.

def fibonacci_naive(n):

if n == 0 or n == 1:

return n

return fibonacci_naive(n - 1) + fibonacci_naive(n - 2)

The time complexity of the naive approach is exponential and therefore a very inefficient algorithm. We will show a top-down DP solution instead. We will want to cache each solution we have in an array \(A\), and only compute a subproblem if it has not been solved yet. So if we come across a subproblem \(f(x)\) that has been solved already, we will check to see if there is a valid value present in \(A[x]\).

def fibonacci_top(n):

A = [-1 for i in range(n + 1)]

return fibonacci_top_helper(n, A)

def fibonacci_top_helper(n, A):

if A[n] != -1:

return A[n]

if n == 0 or n == 1:

return n

A[n] = fibonacci_top_helper(n - 1, A) + fibonacci_top_helper(n - 2, A)

return A[n]

This implementation uses memoization to avoid recomputing subproblems. We initialized the list to contain all \(-1\). Before we ever decide to recurse in some instance, we check if there exists a solution already computed for this subproblem. If so, we return it. Otherwise we recurse to compute it and then store that result for future use. Ultimately, we will end up pruning out entire branches of the Fibonacci call tree. Our time complexity goes from exponential to \(\mathcal{O}(n)\) and our space complexity goes from \(\mathcal{O}(1)\) to \(\mathcal{O}(n)\).

Since top-down is recursive in practice, the code typically follows directly from the recurrence. The typical modification from naive to top-down is to always check the memoization data structure before recursing.

Bottom-Up Approach

The bottom-up approach typically involves starting with our base cases, defining an order of tabulating up the subproblems, iteratively building up to larger subproblems, and ultimately the target problem.

def fibonacci_bottom(n):

if n == 0 or n == 1:

return n

A = [0 for i in range(n + 1)]

A[1] = 1

for i in range(2, n + 1):

A[i] = A[i - 1] + A[i - 2]

return A[n]

Notice how we are still doing memoization here by saving the solutions we computed. But also notice that we are tabulating by iterating across from \(2\) to \(n\). The time complexity is \(\mathcal{O}(n)\) and the space complexity is \(\mathcal{O}(n)\). But we can actually do better. Due to the property of our algorithm only requiring the computation of the last 2 results to compute the Fibonacci number of the next \(i\), we do not need the entire array at any given moment.

def fibonacci_bottom_optimized(n):

if n == 0 or n == 1:

return n

x, y = 0, 1

for i in range(2, n + 1):

x, y = y, x + y

return y

The invariant upon entering any iteration of the loop is that \(x\) is the \((i-2)^{th}\) Fibonacci number and \(y\) is the \((i-1)^{th}\) Fibonacci number. Therefore the \(i^{th}\) Fibonacci number is \(x + y\). We just have to set \(x\) and \(y\) correctly before each new iteration of the loop to maintain that invariant. As a result, the time complexity is still the same as before, but the space complexity is now \(\mathcal{O}(1)\).

Solving 1-Dimensional Problems

When it comes to Fibonacci, the recurrence is already common knowledge. But what if you are given a problem, 1-dimensional in nature similar to the Fibonacci problem, but you are not given a recurrence? Dynamic programming problems, whether in an interview or on a undergraduate exam, are typically framed as word problems. When I say the problem is 1-dimensional, I mean the input is of 1-dimension, like an array. And very likely, your algorithm will also have a 1-dimensional data structure for memoization. The key to solving these problems is to define a recurrence that describes the problem in terms of the subproblems.

Maximum Contiguous Subarray Problem: Suppose you are given an array \(A\) of size \(n\), we want to solve the problem of computing the sum of a contiguous subarray in \(A\) that is the largest sum of all possible contiguous subarrays in \(A\). Our solution will also assume that the array \(A\) contains at least \(1\) element.

Example: \(nums = [-2,1,-3,4,-1,2,1,-5,4]\), the output should be \(6\) because of \([4,-1,2,1]\).

It is not an easy task to define a recurrence to solve such problems. My biggest advice is to apply a strict English definition to each recurrence you create, that defines what it returns based on the inputs. This will take a lot of practice, but seeing some examples first hand will help. An approach to this problem (credit to Robbie Weber’s lecture slides) is the following recurrence definitions:

-

\(INCLUDE(i)\) is the maximum sum of a contiguous subarray among elements \(0\) to \(i\) that includes the element at index \(i\).

-

\(OPT(i)\) is the maximum sum of a contiguous subarray among elements \(0\) to \(i\).

Notice how \(OPT(n - 1)\) will give us our solution, as it would find us the maximum sum for some contiguous subarray among elements \(0\) to \(n - 1\). And further notice how \(INCLUDE\) is the same definition as \(OPT\) but with a strict condition that it must include element \(i\). It is often the case that we might need to define a stricter definition of the optimum recurrence to help us write a solution for \(OPT\). Moving from the English definitions to the mathematical representation, we can easily achieve the following recurrence:

\[INCLUDE(i)= \begin{cases} max\{A[i], INCLUDE(i-1) + A[i]\} & \text{if } i \geq 0\\ 0 & \text{otherwise}\\ \end{cases}\] \[OPT(i)= \begin{cases} max\{OPT(i-1), INCLUDE(i)\} & \text{if } i \geq 0\\ 0 & \text{otherwise}\\ \end{cases}\]\(INCLUDE(i)\) makes logical sense from the English definition. The maximum sum of a contiguous subarray ending at \(i\) is either the maximum sum of a contiguous subarray ending at \(i - 1\) plus \(A[i]\), or it is simply \(A[i]\). \(OPT(i)\) also makes sense from the English definition. The maximum sum of a contiguous subarray among the elements from \(0\) to \(i\) is either the result of the maximum sum of a contiguous subarray among elements \(0\) to \(i-1\), or it is the maximum sum of a contiguous subarray ending at \(i\).

How did we get here? We defined our problem with a recurrence \(OPT\) that defines the optimum, in which the English definition with the questioned input, gives us the answer to all of our worries. But then we realize that we might have to solve subproblems of the problem, possibly with stricter definitions, so we created an additional recurrence to guarantee that its optimal value is based on the inclusion of \(A[i]\) in the subarray for some \(i\) input. This allowed us to reach the following recurrence. Translating from English to mathematical recurrence definitions may be hard, but it is a matter of thinking of the cases involved as well as how to chain together our recurrences in a logical manner. This is where mathematical induction may be a useful prerequisite.

My personal tip to moving towards a programmatic solution is to have a memoization data structure for each recurrence you defined. Of course this is not entirely necessary as we will soon see. But our naive bottom-up solution for this is the following:

def max_subarray_sum(nums):

n = len(nums)

include = [float('-inf') for i in range(n)]

opt = [float('-inf') for i in range(n)]

include[0], opt[0] = nums[0], nums[0]

for i in range(1, n):

include[i] = max(nums[i], include[i - 1] + nums[i])

opt[i] = max(opt[i - 1], include[i])

return opt[n - 1]

The algorithm is what you would expect given the above tip. I have an \(n\) element array for caching the results for \(INCLUDE\) and I have an \(n\) element array for caching the results for \(OPT\). The loop looks identical to the recurrences, and my final answer is the final element in \(OPT\). As we can see, applying the English definition from earlier we get: “\(OPT(n-1)\) is the maximum sum of a contiguous subarray among elements \(0\) to \(n-1\)”. This perfectly describes the problem we wanted to solve. It works with \(\mathcal{O}(n)\) time and space complexity.

Yet we can still become more optimal in our solution by realizing that we only needed the optimal so far and the optimal that ends at \(i\). Thus we get the following:

def max_subarray_sum_optimized(nums):

n = len(nums)

include, opt = nums[0], nums[0]

for i in range(1, n):

include = max(nums[i], include + nums[i])

opt = max(opt, include)

return opt

This improves our space complexity to \(\mathcal{O}(1)\).

So the summary for 1-dimensional problems is to consider some new element \(i\), and assuming we’ve solved everything from \(0\) to \(i-1\), we use the optimal solutions found between \(0\) and \(i-1\) to solve for \(i\). And each step forward will use the solutions found before. This sounds awfully like mathematical induction, because it is suppose to. I recommend learning about this mathematical proof technique for further insight into this type of thinking, as well as for the benefit of being more sure in your algorithm’s correctness.

Solving Multi-Dimensional Problems

Dynamic programming really shines in multi-dimensional problems. These are problems where \(OPT\) has more than one input. Typically, each dimension has an explicit meaning. In such cases where we do memoization, we will have a dimension to our data structure for each dimension present in the problem.

The maximal square problem is described as finding the area of the largest square of 1’s in a given matrix containing only binary digits. The following matrix should give us a maximal square area of \(4\).

\[\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 1 & 0\\ 0 & 1 & 1 & 0\\ 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 \\ 0 & 1 & 1 & 0\\\end{bmatrix}\]The key hint to finding a recurrence is to once again, define a good English definition of \(OPT\). Though the average beginner to dynamic programming will need a much bigger hint for this problem. Consider a cell in the matrix, \(M[i, j]\). We can describe the problem as finding the maximal square whose corner is \(M[i, j]\). Then if we were to solve this problem at every cell, then we can get a maximal square. But where does the dynamic programming attribute of having overlapping subproblems come in? The following recurrence reveals the key insight into the problem.

\[OPT(i, j)= \begin{cases} M[i][j] & \text{if } i = 0 \text{ or } j = 0\\ 0 & \text{if } M[i][j] = 0\\ min\{M[i-1][j], M[i][j-1], M[i-1][j-1]\} + 1 & \text{otherwise}\\ \end{cases}\]\(OPT(i, j)\) is defined as the length of the maximal square whose corner is \((i, j)\). The insight is that the length of this square is dependent on the optimum of its \(3\) adjacent neighbors, \(M[i-1, j], M[i][j-1], M[i-1][j-1]\). If \(M[i, j] = 1\) and \(OPT\) of its neighors are \(3, 4, 5\), then the best we can hope for is \(3 + 1\), as the largest square whose corner is \(M[i, j]\) is only as good as its weakest neighbor. If one of our neighbors is a \(0\) but \(M[i][j] = 1\), then we cannot be a corner of a bigger square.

Due to the limited definition of our recurrence, we are only computing the length. And due to the limited definition, a call to \(OPT(n-1, m-1)\) will not give us our solution, as the maximal square might not have \(M[n-1][m-1]\) as its corner. The following is one possible solution.

def maximal_square(M):

if len(M) <= 0:

return 0

maximum = 0

row = len(M)

col = len(M[0])

opt = [[0 for j in range(0, col)] for i in range(0, row)]

for i in range(0, row):

for j in range(0, col):

if i == 0 and j == 0 and M[i][j] == '1':

opt[i][j] = 1

elif M[i][j] == '1':

opt[i][j] = min(opt[i-1][j-1], opt[i-1][j], opt[i][j-1]) + 1

else:

opt[i][j] = 0

maximum = max(maximum, opt[i][j])

return maximum**2

Before we can compute any given cell, we have to compute its \(3\) neighbors. The order in which we approach our bottom-up approach matters. The algorithm’s time and space complexity performs in \(\mathcal{O}(mn)\). As we see from this problem, it is often the case that the recurrence is more difficult than the translation to an algorithm. We want to be able to single out a single element or cell of our input and describe a problem \(OPT\) for that element. This element that is singled out is given a unique property in the problem, typically on the edge of some frontier, in this case it is the corner of the candidate square.

Conclusion

There’s no easy way around it. You have to practice. There are problems that will buck any prior intuition you had about the patterns that show up in DP problems. It’s hard and takes some practice to get better at. There are problems where DP is not the first instinct you might have. There are problems where DP is your first instinct, but isn’t the optimal solution or even a solution at all. For further practice, I recommend tackling some of the following problems on leetcode. Good luck!

Problems for further practice:

Problems covered in this blog post: